The Wrong Stuff Read online

Page 2

My father was an extreme conservative. Still is. He believes FDR gave everything away and caused all the economic problems we are having now. He’s a Republican and a devout Catholic. I view that as a contradiction in terms. It was my religious beliefs that caused me to take a liberal stance on issues. I believe in the corporal acts of mercy, in giving to people who don’t have anything. If you take care of those around you, you end up taking care of yourself, because you establish a good pattern of karma.

It was my maternal grandfather’s love for the environment that helped shape my concern for the earth’s well-being. Grandfather was an ecologist of sorts and was very intense about it. He used to run litterers off the road with his car. He also felt motorboats were polluting the lake near his home, so he used to sit on the shore and root for the water skiers to crash into each other. I had a lot of conversations with him, and he taught me a great deal about life, passing down the things he had learned from my great-grandfather Rockwell Dennis Hunt. Great-grandfather was a historian and dean of the USC graduate school for thirty-five years. His intelligence was awesome, but he did, to some degree, inhibit my learning experiences as a child. He used to sit me on his knee and tell me how he would hunt swans on the Sacramento River in the 1880s. That was his favorite story, and after the tenth retelling, it started to get to me. Pretty soon, every time someone picked me up and put me on his knee, I automatically figured, uh-oh, here comes the swan story, so I would wink out and not hear a word they said. This probably closed off a whole avenue of education for me.

My father always told me, “Ask a lot of questions or you’ll never learn anything.” But I was unusually quiet in grammar school and throughout most of high school. I never had any girl friends back then. Two missing front teeth were part of the reason. They made me shy and embarrassed; I developed the habit of talking with my hand in front of my face. I was honestly afraid of girls and couldn’t play any of their games. They wanted to go to movies and dances. I just wanted to run around trees. Making out just didn’t seem to be a very productive way to spend time. I made up for that later. Actually, that shyness was probably a good thing. If I had gotten my sexual aggression out earlier, I never would have made it as a ballplayer. I would have fallen by the wayside and had three kids of my own by the age of seventeen.

One of the reasons I didn’t, besides my own bashfulness, was the attitude of coaches toward sex. We were taught to fear sex as something that would rob us of our stamina. The word was, “Tiger, if you let women drain away your life’s essence, you’ll never be able to go nine.” Some of that mythology has carried over to the pros. The Red Sox brass were always telling Sparky Lyle that if he kept screwing around he would lose his fastball. They claimed it would float right out of his dick. Later he told me they were right, but that they forgot to mention how it would add all sorts of movement to his slider and carry him to the Cy Young Award.

My early formal education was really quite ordinary up to high school. I had been in a three-year junior-high-school program in Southern California and transferred to a four-year high-school program in Northern California in my sophomore year, enrolling in Terra Linda High.

Coming to Terra Linda was a traumatic experience that actually paid some dividends later on. When I arrived there I found their system wasn’t in sync with the one I had just left. They told me that even though I was old enough to be a sophomore, I still had to take some freshman classes in order to fullfill their requirements. So half my classes were on the sophomore level and the other half were for freshmen. I ended up caught between two cultures. My soph class was made up mostly of fifties rockers, while the freshmen were the eventual flower children of the sixties. It was like being stuck between two time warps.

I also went through some culture shock. All the kids in Northern California wore really tight pants with cuffs up around their ankles. Very punkish. I found out later that the reason for this style was the wind coming in off the Pacific. It would blow up their legs and freeze their nuts off in winter. We never worried about cold weather in Southern California. People in the north would huddle in groups for warmth and would end up sharing thoughts and concepts. Down south we didn’t care for crowds. Too sticky. We preferred one-on-one relationships. Being exposed to what was essentially a whole new world while still in my teens helped to raise my consciousness. It made me more tolerant of others and more open to change in myself.

Another big difference between the two cultures was their attitudes toward war and violence. Northern California was dove country; the southern part was populated by hawks. Most of my freshman class would later become part of the peace movement in the sixties. They made me aware of a life outside my own. I started to read political literature and began to listen to music in a new and different way. A group of us would go to concerts at the Fillmore West. I remember seeing Jim Morrison and the Doors there. It was extraordinary, watching him as he swayed back and forth, clutching the microphone as if it held the secret to life. He was the Lizard King holding court. I liked his sense of poetry and the way he delivered his songs. The voice was shot, really wasn’t there anymore. But there was something awesome in the way he paused. It was as though he would set himself in a trance, view a world only he could see, and then come back to earth to report on it. The Joshua Light Show was going on in back of him, swirling amoebas on a screen, and after a while it looked as if my brain cells were bleeding out of my eyes. When we left, we watched as sparks flew out from under our shoes. They had sprinkled phosphorus on the floor. I hadn’t done any drugs, didn’t really know what they were yet. Didn’t matter. Just being in there got you high, like being a nonsmoker at a cocktail party. It was one of those San Francisco nights that helped shape my formative years.

I started to look for messages everywhere, in songs, books, and movies. I realized everything had its own message. In 1969 I saw Easy Rider with several members of the Red Sox. They thought it was a movie about drugs and sex, but I knew otherwise. It was a movie with a very specific message: Don’t ride a motorcycle through Georgia while wearing an American flag as a jumpsuit. That’s something I’ve never quite forgotten.

The sports program in high school was very limited. All we had was baseball and basketball. We couldn’t have any other sports; the school was only two years old, and we only had freshman and sophomore years to draw talent from. I didn’t go out for basketball that first year—I just didn’t have the confidence. That’s a shame, because I really grew to love basketball, almost as much as baseball.

I did try out for the baseball team right away and had no trouble making the squad. I was able to throw strikes right from the start. The team came in second in our conference, surprising a lot of people. No one expected us to do that well with the small universe of players we had to draw from. I had one of the better records in the conference, but no one seriously scouted me because I didn’t throw hard. That was a problem. Scouts, on both the pro and the college level, just love to see those big studs who can throw the ball through the wall. This often causes them to overlook the finesse player who really knows how to pitch. I was your basic fastball, curveball, changeup pitcher. The breaking ball was my biggest asset and had been for a long time. My father had taught me how to throw a curve and a knuckler when I was eight.

He also taught me to change speeds, preaching that hitting was timing and that the successful pitcher could upset that timing. Since I could change speeds and get my breaking ball over, I was able to win a lot of games in high school.

It was about this time that I became aware of the preferential treatment that athletes automatically receive, even on the high-school level. We could cut certain classes and get away with a little bit more than the average student. Or even the above-average student. It’s no wonder that our priorities got screwed up. Just because a person can throw a ball harder or hit it farther than most ordinary human beings, he is placed on a pedestal at an early age. I don’t think there is anything wrong with admiring an exceptionally

skilled person, but the hero-worship we shower on athletes goes beyond that. This is a part of the tribal influence handed down by our ancestors. Man has always been lionized for his physical prowess. An Indian brave did not have to pass a math quiz in order to become a chief, he just had to tear the ass off some bear. And the twelve labors of Hercules did not include a Regents’ exam. Society has tended to find its heroes in the most obvious arenas, and I don’t regard that as a healthy thing. We should find our heroes in the bathroom mirror each and every morning.

Graduating from Terra Linda in 1964 brought me face to face with the first big decision of my life. I had to choose a college. I was not yet seriously considering a career as a ballplayer. The odds were too great against it, and I wasn’t sure it was what I wanted to do with my life. I had worked part-time with my Uncle Grover as a locksmith. He was a good friend of Howard Hughes and used to do a lot of work for him. Hughes would call him up at three in the morning and have him change all the locks in one of his studios. One time I went with Grover on a job at one of Gene Autry’s hotels. We changed 165 locks and charged $8,000. The materials cost $150. I took one look at that and said, “Shit, who needs baseball. This is great.” But by the time the summer was over I decided that locksmithing would just be my safety net, something to fall into if some other things didn’t work out.

My mother was pushing for me to become a dentist, but I didn’t think I could handle that. That’s a profession with a very high suicide rate. Which is understandable. You spend hours on your feet digging five-day-old frankfurter out of somebody’s mouth, and you’re bound to get depressed. I wanted to be a forest ranger. I had a yearning to sit up in one of those towers and look after thousands of evergreens. That seemed peaceful and worthwhile. But in the back of my mind, I did want to give baseball a fair shot. I considered going to Humboldt State College because it was the only college in California that had a forestry program. My family wouldn’t hear of it. With a great-grandfather who had served as dean at USC and a lawyer uncle who was still a leading member of their alumni association, I was expected to uphold the family tradition and go to the University of Southern California. The only problem with that was the university didn’t have a forestry program. I was at a crossroads. Would I become a forest ranger and live forever with pent-up guilt over not pursuing a baseball career? Or would I become a baseball player with pent-up guilt over my failure to protect the sons and daughters of Bambi? I thought I could compromise by going to the University of Oregon and exploring both possibilities, but my father straightened me out, saying, “Son, face the fact that you want to be a ballplayer. Now, do you want to be a big fish in a little pond? Or, do you want to go to SC and be a little fish in a big pond and accept the challenge of eating your way up into becoming a big fish.” I liked challenges, so I went to SC and gobbled up people left and right. And I still didn’t get scouted.

I was hoping to get an athletic scholarship, but the school wouldn’t grant me one. I had gone up to speak to the baseball coach about it the summer before my admission. That was my first meeting with Rod Dedeaux. After hearing the reason for my coming, Rod shook his head, saying, “Tiger, tiger, you have to prove yourself here. Nobody buys a car sight unseen. Get on the freshman team, win some ballgames, and then we’ll see what we can do for you.” Rod called everybody Tiger. I don’t think he knew anybody’s first name. If he did, he wasn’t letting on. Fortunately, I was able to get an academic scholarship because my grades were high and I had gone to a progressive school. Terra Linda was considered progressive because we didn’t have any school bells. We just floated around the building from class to class.

During that first year I made the team and went 9–2, but my grades were dropping and I was placed on probation. My ERA and my grade-point average were exactly the same: 1.92. I was in predentistry out of deference to my mom, but I couldn’t hack it. I lost my academic scholarship but was switched over to an athletic one because I could get people out. After a semester of staring at pictures of decayed molars and inflamed gums, I also changed my major to geography.

My early days at SC were mildly upsetting. It was my first time away from home, and the dormitory was in the middle of Watts. All we kept hearing about was how tough the neighborhood was and how high the crime rate was. The statistics really struck home on the very first weekend, when my friend Freeman and I were all set to cruise Hollywood in his ’63 Impala. We were dressed to kill, with our best jeans and sports jackets, hair slicked back with Brylcreem, and two quarts of Aqua Velva between us. We were ready to tear the town up. Racing from the dorm, we felt like modern adventurers out of Route 66. We flung open the doors of the Impala, jumped into the car, and fell into Freeman’s trunk. Someone had made off with his interior. There was nothing left, not even an ashtray. We ended up driving along the Sunset Strip, sitting on orange crates.

I have to admit to homesickness those first couple of weeks, but I was lucky. The baseball was a calming influence. I had never seen anybody like Dedeaux. By our first game I was convinced he was the greatest manager who had ever lived. He was a good friend of Casey Stengel and had learned a lot from their association. Casey taught Rod to be a master psychologist, able to convince his team that there was no way they could lose. Dedeaux used to tell us, “Don’t be concerned with winning. That’s not good enough. Play to achieve perfection.” He figured winning was the by-product of the quest for perfection.

My first time on the mound he taught me another important lesson. I was in the process of semi-intentionally putting the winning run on base, confident I could get the next hitter out. Before I threw my second ball, Rod was racing out to the mound, demanding to know what I was doing. I told him I thought I would have an easier time with the next batter. He put his arm around me and said, very seriously, “Tiger, that’s where you’re making your first mistake. Never think. It can only hurt the ballclub.”

Dedeaux is from Lousiana and has a French background, but he always had us singing “McNamara’s Band” after each victory or before a crucial game. He had heard Dennis Day sing it years ago and once had his team belt it out before an important series that they went on to win. He’s been using it ever since. There are many times that I am convinced he’s just a frustrated Irishman.

It’s only in the last ten years or so that people outside of California have become aware of him. That’s because, despite a great record at USC, Rod was never much interested in self-promotion. All he cares about is promoting baseball in general and Trojan baseball in particular. He’s a great man. He could probably command an astronomical salary from any major college, but at SC he works for nothing. Rod is a very successful businessman, and he donates his time to the school gratis. That’s how much he loves the game. Rather than take money out of the baseball program for himself, he prefers to use it to make sure that his boys travel first class all the way. I’ve heard more than one of his players say that, in a lot of ways, going from SC to the minor leagues is a demotion.

Rod always had good teams, so good that when Don Buford played for him he wasn’t really a starter. He was what Rod called a Double X’er, which is the same thing as a utility man in the majors. This is the same Don Buford who starred on three American League championship teams with the Baltimore Orioles, batting lead-off and playing left field.

The secret to Dedeaux’s success was his strict adherence to fundamentals and his ability to maximize a player’s strengths while minimizing his weaknesses. I have a quirk in my body: I can’t throw two pitches in a row at the same speed, no matter how hard I try. I also can’t throw the ball straight; it either dips or rises. Rod knew I wasn’t about to overpower anybody, but he saw that I had a good command of my pitches and that I had pretty good stuff. I might not be able to throw the ball by too many people, but I could break your bat with a sinker. Rod continued the teachings of my father: throw strikes and keep the ball low. He also made me work on my fielding, realizing that I threw a lot of ground balls and would have to be able to h

elp myself with the glove.

Dedeaux was known as the Houdini of Bovard because USC played their home games at Bovard Field and his teams were always pulling off miraculous escapes from defeat at the last minute. Years after my time SC was playing the University of Minnesota in a semifinal round of the College World Series. Dave Winfield was pitching for Minnesota, and he had a one-hit shutout and a 7–0 lead going into the ninth. The only hit off him had been an infield roller. SC got up in the bottom of the ninth and scored eight runs for the ballgame. They got five consecutive pinch hits in the last inning. I was pitching for the Red Sox against the Angels in Anaheim that night, and they were carrying the linescore for the SC game on the electric scoreboard. Everyone went nuts when that big eight went up. Didn’t surprise me. That was Rod. This was just another example of his team’s knack for coming back and ripping out the opposition’s heart.

Of course, I had seen Rod’s influence firsthand, the way he made you believe you were in a temple the moment you stepped in between those white lines and how he had everyone do his job with maximum effectiveness in order to get positive results. It paid off. In each of my four years at SC, we always were able to field a competitive squad. We were eliminated in the National Championships in 1966. Barely. The next year we didn’t make it, having been beaten out by UCLA. They had a first baseman named Chris Chambliss who used to eat my lunch. He was the same kind of hitter then that he is now, an alley hitter with line-drive power. The thing that impressed me most about him was his uncanny ability to wait on the ball. I guess that’s why he would kill me; I wasn’t quick enough to put the fastball by him. He’d fight it off and hit jam shots over second. Or, if I hung a breaking pitch, he’d step back and . . . yak-a-tow! There it went over the far reaches of the Pacific Ocean.

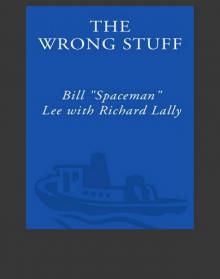

The Wrong Stuff

The Wrong Stuff